Daisy Gummere originated from New Orleans, but was born in Philadelphia on May 12, 1863. Her first husband was Andrew Simonds (1861-1905), founder and President of the First National bank of South Carolina, who gave Daisy O’Donovan Breaux a Beaux Arts/Renaissance Revival mansion called Villa Favorita in Charleston as a wedding present. In 1907 she married Barker Gummere, a New Jersey Banker, and in 1918 Clarence Calhoun (who died in 1938). She died on March 21, 1949.

In 1892 the Philadelphian painter Augustus George Heaton painted a portrait of this sitter, which in 1996 was the property of her grandson Charles W. Waring in Charleston, South Carolina.

Bibliography of sitter:

Daisy Breaux: The Autobiography of a Chameleon

Susan LeGree: Finding Roses in the Clouds (2009).

—

Mrs Gummere and Muller-Ury at White Sulphur Springs in August/September 1916.

The Washington Times, Wednesday evening, November 26, 1919 tells the story of the commission in the artist’s words:

‘At a certain dinner party at the home of Mrs Lewis Nixon, April 14, 1916, the then Mrs Gummere requested me to paint portraits of herself and of her daughter, Miss Marguerite Simonds, and I agreed to do so, it being understood between us that I was to be paid my regular standard price therefore.

Muller-Ury, Mrs Gummere, and her daughter Margaret Simonds at White Sulphur Springs, August/September 1916. Muller-Ury is carrying the dog he would include in Miss Simond’s portrait.

‘Subsequently, at the request of Mrs Gummere, I went to White Sulphur Springs, W. Va., for the purpose of painting the portraits. Mrs Gummere and her daughter gave me frequent sittings. I worked on the portraits continuously from August 23, to September 18, 1916. Some time in September, 1916, Mrs Gummere gave a tea in which she invited a number of her friends to see the partly finished portraits. She then and there expressed herself as being well pleased and satisfied with them.

The artist with Mrs Gummere and Miss Simonds at White Sulphur Springs in August/September 1916.

In November 1916, Mrs Gummere had photographs made of the portraits for the purpose of distributing them among her friends. I finally complete the portraits in March 1917 and sent them to Mrs Gummere, at her request, to Charleston, S. C. She accepted and retained them.

During my visit to White Sulphur Springs, I was given a commission to paint a portrait of a niece of a Mrs Flagler. As Mrs Gummere claimed to have been instrumental in having such commission given me, I agreed to allow her a special discount of $1000 on her daughter’s portrait, thereby reducing the price thereof from $3500 to $2500 leaving the amount due to me for the two portraits to be $6000, instead of $7000.’

So clearly Muller-Ury painted Mrs. Gummere and her daughter Margaret Simonds at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia in the summer of 1916, where he was photographed with both Mrs. Gummere and her daughter, and finished them in his New York studio in December that year, when Mary Hopson took photographs of the portraits for Mrs. Gummere to give to her friends as Christmas presents.

A letter in the Knoedler Library dated December 26, 1916 (Domestic Letterbook December 2, 1916—January 17, 1917, No. 256), reads as follows:

‘Dear Sir

We enclose herewith copy of a letter which we received from Mrs. Barker Gummere of Charleston, S. C. concerning the frames which you had us bill her several days ago. She is paying the bill with the understanding that she may return the frame on her portrait, which is the one you ordered for her. We thought before acknowledging receipt of her check that we had better take the matter up with you, as you are aware that the old frame would be of little use to us.

Awaiting your reply, we remain,

Very truly yours

M. Knoedler & Co., F. G. McMann.’

In a letter to Roland Knoedler of February 19, 1917 (original in the Knoedler Library), Muller-Ury wrote:

‘Will you kindly tell your bookkeeper to send to me the cheque for the amount collected from Mrs. Gummere for a frame & settle my bill — as she likes both frames now.’

The artist sent the pictures to Mrs. Gummere’s home in Charleston, and a year passed without the artist being paid. He then requested something on account. When Muller-Ury went to law is unknown, but The Washington Post reported in March 1920 that Mrs Daisy O’D Breaux Calhoun of 1529 New Hampshire Avenue had answered Muller-Ury’s suit in the District Supreme Court yesterday saying that the artist had promised her that if the paintings were not satisfactory she would not have to pay for them ($6000):

‘Attorney Frank J Hogan represented Mrs. Calhoun. Her answer declared that the claim of the artist that he had painted distinguished persons in this country and Europe was made merely for the purpose of publicity and self advertising. She denied ever having asked the artist to paint her likeness and declared that it was only after his persistent requests to paint her that she consented to sit for the painting. Referring to the portraits which were painted at White Sulphur Springs in the summer of 1916 Mrs Calhoun says they are unrecognizable. Mrs Calhoun says that her friends bear her out in this statement.’

Town Topics reported in October 1921 the artist was to sue for the cost of these portraits ($7000). According to the The Washington Times, Wednesday evening, November 26, 1919, p. 2, the artist claimed 6 percent interest from April 1, 1917, besides costs. He apparently instructed Attorneys McKenney & Flannery.

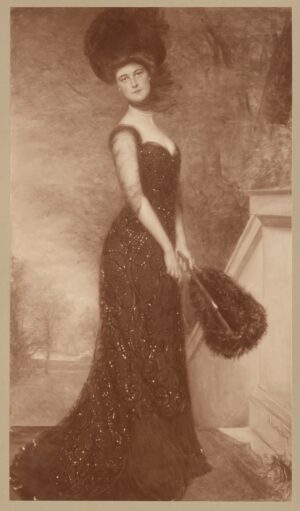

The photograph of Mrs Gummere which Muller-Ury stuck in his photograph albums in 1916.

According to the sitter’s grandson, Charles W. Waring (written communication to the editor July 24, 1996), his mother told him that his grandmother did not like Muller-Ury’s portrait “because it made her look like a pneumatic tire” though he believed that it hung in her Maryland house when he was a boy. It can’t be denied that Muller-Ury somehow failed with this portrait, judging by the posed photograph of Mrs Gummere in day dress he stuck in a photograph album (artist’s papers), and it’s difficult to comprehend why; it would appear that he sought to flatter the sitter, and in his interpretation of her features smoothed her skin and made her look fat; maybe the dress and the pose somehow seemed appropriate in White Sulphur Springs but not elsewhere; or is it that Muller-Ury failed to notice the self-styled ‘chameleon’ nature of the sitter. Taking the incomplete pictures back to New York to finish and not having the sitter in front of him cannot have helped, but then why was Mrs Gummere apparently happy to hold a tea to show the pictures to her friends and send photographs of the completed portraits to her friends?

It is nevertheless difficult not to conclude that Mrs Gummere, a social climber if ever there was one, who made three marriages to her considerable financial benefit, was using the artist for comparable aims; he was in Washington, of course, in 1916 to paint the First Lady, Edith Wilson, and on its successful completion he received great publicity, and she probably felt that there would be some social benefit from having her portrait made by him so shortly afterwards. Whilst it is true that at White Sulphur Springs he received a commission for the portrait of Louise Wise, niece of Mrs Flagler-Bingham (one of his most beautiful works completed in January 1917), the evidence would appear to be that Mrs. Gummere had no intention of paying for the works – even if she eventually paid for the frames in December 1916, her indecision over which ought to have been a warning to the artist that all was not well. The three years that it took the artist to decide to sue Mrs Gummere certainly suggests the artist hoped she would eventually pay but in the end lost patience, and Mrs Gummere must have thought that any bad publicity would not be good for the artist – but post-war American society had changed completely and this was no longer the case. He was too well established now for this to affect his career. The lawyers must have persuaded both sides in a compromise, and Mrs Gummere appears to have retained her own portrait, and the artist took back that of her daughter Margaret Simonds which remained in his studio until he died.